Tomorrow marks seven years since my late wife Linda Cudworth died after eight years of survivorship through ovarian cancer. The diagnosis came as a shock, as did multiple episodes of recurrence. Each time we’d reel from the news, go back into treatment and compartmentalize the best we could by using the phrase, “It is what it is.”

Those last months during the winter and spring of 2013 were confusing because doctors treating her for seizures learned there was a tumor in her brain. I’ve never published photos of her during that last round of radiation treatment because while we made the best of it, snapping pics using my laptop Photo Booth and laughing as the absurdity of it all, it was a strange world we were about to enter, because ovarian cancer was not supposed to be able to pass through the blood-brain barrier. But it did.

We treated it with radiation and she started a regimen of steroids to contain the swelling and her personality became magnified. She lost native inhibitions about many things. On one hand, that was disorienting, as it ultimately became impossible for her to continue teaching at the preschool she loved. On the other hand, it proved to be liberating as she used those final bursts of steroid-fueled energy to buy a beautiful piece of art. She also stayed up late at night to research and buy a new car even though she abhorred going online. In sum she lived life to the fullest, however manic it might have been.

And that was bittersweet. Because when the steroids stopped, so did her energy. She passed away a few weeks later in the company of her husband and two children. Still, she never lost her sense of humor. After I’d arranged for palliative care in our home, we moved her from our master bedroom to the hospital bed in the living room where nurses and such could tend to her properly. The journey from bedroom to living room was awkward and difficult given her weakened state, but she looked up at me once she was tucked into the cover and smiled while saying, “I thought I wasn’t supposed to suffer.”

Most of that was indignity, and my late wife was a person who believed and abided in dignity in all she did. It was part of her beauty as a person. She also respected propriety, which made it amusing to think back on the fact that I showed up a night early for our first date. “What are you doing here?” she asked. “Our date is tomorrow night!”

She agreed to go out for a short dinner before hosting her parent-teacher conferences at the high school where she taught special education. But before we parted that evening, I got a taste of her naturally biting humor in reminding me that I ought to call confirm a date.

We got to know each other a little that evening and followed up with a hike to Starved Rock State Park. Stopping on a high ledge for a picnic on a mild November day, she broke out a lunch of apple-walnut bread sandwiches, cheese and wine served from a leather-covered flask. That implement was a remnant of her high school hippie days.

We dated four years and even survived a long-distance romance early on when I was transferred from Chicago to a marketing position in Philadelphia. She visited me on Thanksgiving that year despite her mother’s objections, and I moved back to the Midwest the following spring when the company decided to disband the entire marketing department due to misguidance by the Vice President.

That would be one of a few job upheavals experienced over the years, and we survived them all. Our children came along in our late 20s and early 30s. Soon our lives were immersed in preschool, elementary adventures, and all the way through high school performances in music and drama.

We also belonged to the highly conservative church synod in which she’d grown up. The pastor that married us at the time was, however, a grandly considerate and patently open-minded man that once gave a sermon titled, “Do-gooders and bleeding hearts : Jesus was the original liberal.”

Our lives swirled with church activities as our children passed through Sunday School all the way to confirmation, where they roundly passed the tests despite having to choke down conservative ideology about evolution preached by the pastor that had long-since replaced our marriage counselor.

After 25 years we moved up the road to a more tolerant and progressive Lutheran church. It was gratifying to learn that our friends from the former church did not abandon us. In fact without their help and the guidance of one of Linda’s best friends, a woman named Linda Culley, we would not have had as much grace and good fortune in the face of the perpetual challenges served up by cancer survivorship.

Now what I like to think about are the camping trips we took to the north woods while dating, and later, when we had small children, we’d spend a week each summer at a humble resort called 7 Mile Pinecrest thirteen miles east of Eagle River, Wisconsin.

Our children paddled around in the water and slipped off to Secret Places in the woods while their father fished in the early and late hours and went for runs half-naked in the pine woods north of the resort, swatting at deer flies the entire time.

At the center of all that family joy and adventures was Linda, whipping up sandwiches and sitting with a glass of wine on the small beach overlooking the lake. That was the only time the Do Not Disturb sign seemed to rise on the Mom Flag.

And when we weren’t visiting or traveling or doing school activities, Linda was immersed in planning, purchasing and planting her garden every year. Her priorities were indeed God, Family, and Flowers.

She was a really good person. That’s what so many friends have told me over the years. I was married to a really good person, and that makes me think of what a close friend told me when he first met her. “This is a good one, Cuddy. Don’t let her get away.”

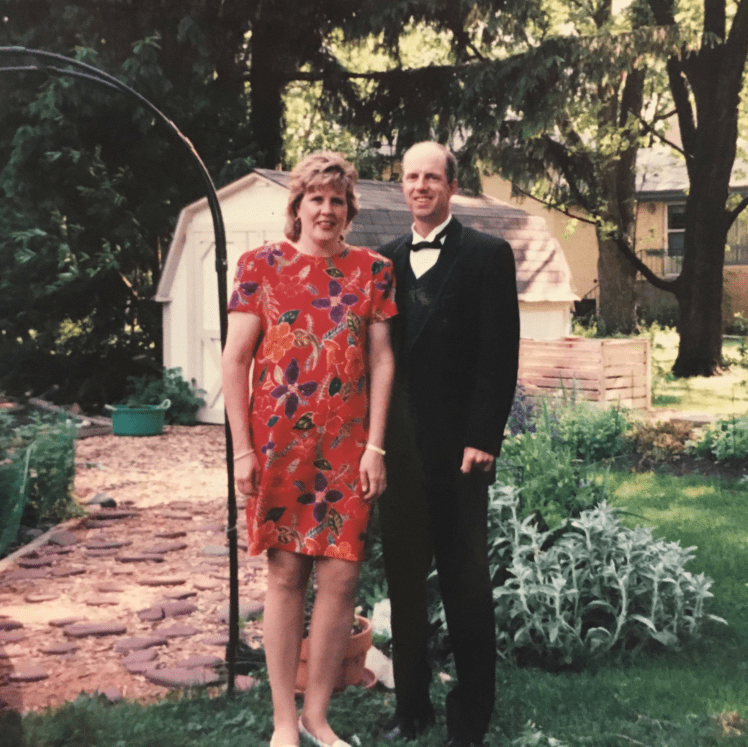

It is bittersweet and sweet to think about all those years together. My daughter went through our stacks of photos to digitize the images and I’ve waited until today to open it up and pull some memories out to post with this blog. Holding people close to your heart is first and foremost the right kind of pride. I hope this writing inspires you to consider the importance of people in your lives.

And to realize as well that life does go on. She told our close friend Linda Culley that she knew, if she were to pass away from cancer, that I would meet someone again. And I have found love. But it does not mean the years with Linda Cudworth are forgotten. Far from it.

These memories can lift us up. Give us courage to go on. Cherish the life we had as well as the life we have. And that is the right kind of pride as well.

But it was stressful. Sometimes we’d be pressed financially, and it was on one of those nights that we added up the bills, said our prayer and got her into bed to rest.

But it was stressful. Sometimes we’d be pressed financially, and it was on one of those nights that we added up the bills, said our prayer and got her into bed to rest.