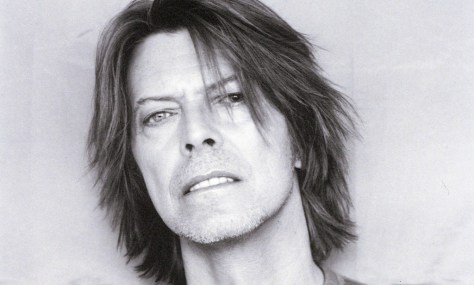

We read news of the death of David Bowie from cancer and what does it tell us? That he “lost his battle” with the disease.

It’s time for some changes in that sort of language. I’ve watched several people dear to me die from cancer, and they did not lose the battle. They won time instead.

Time to live. Time to consider the importance of the people they loved. Time that mattered.

Cancer is an indiscriminate condition that can cause death eventually. You don’t get it because you’re a bad person, but bad habits like smoking can cause it. Yet cancer can also come along because you’ve spent too much time in the sun, or had the bad luck to carry a certain cancer-causing gene. So to suggest that you’ve lost the battle is to make a pitch that the battle was lost before we ever knew it was begun.

Well, that’s rather true for all of us, isn’t it? Life itself is a pre-existing condition. Yet in defiance of that truth, we’ve all been living with a health insurance business that parses that fact for its own profit. And we deal with drug companies that jack the price of life-saving drugs simply because they can. It goes on and on.

Pushing through the market square,

So many mothers sighing

News had just come over,

We had five years left to cry in

News guy wept and told us,

Earth was really dying

Cried so much his face was wet,

Then I knew he was not lying

That means it can be an expensive battle to live, to pay for the right to continue one’s life. That’s immoral on its own, of course. But every time someone dies from cancer it seems we repeat that meme about “losing the battle” ad hominen (against the person that died) and ad infinitum (there but for the grace of God go I.)

So stop it. Make the ch-ch-ch-change in yourself when you speak of someone dying from cancer, or any other reason. They did not lose a battle against a disease or anything else. They won time to the best of their ability. And we should all honor that.

So stop it. Make the ch-ch-ch-change in yourself when you speak of someone dying from cancer, or any other reason. They did not lose a battle against a disease or anything else. They won time to the best of their ability. And we should all honor that.

As for the memory of David Bowie, many of us had no idea he was sick. But even famous people deserve privacy. Perhaps something reached out to me through the cosmos however, because two weeks ago I printed out a bunch of chordsheets of his music and began playing his songs. Moonage Daydream is a tremendously cathartic bit of music to rip on guitar. It brings us back to those moments in life when music props us up against the perceptions of the world.

Bowie and I go back to the Ziggy Stardust album, which I revered as a sophomore in high school. The androgyny of the character and his person both fascinated and terrified me. At the time, it was not acceptable in any form to be considered feminine by those terms. Not in the tiny farm town where I lived.

Bowie and I go back to the Ziggy Stardust album, which I revered as a sophomore in high school. The androgyny of the character and his person both fascinated and terrified me. At the time, it was not acceptable in any form to be considered feminine by those terms. Not in the tiny farm town where I lived.

I didn’t necessarily have the instincts to publicly display my curiosities. But like many young men I tucked my manhood between my legs and looked in the mirror wondering what it would mean to look like or be a woman. I have photos from that period when my facial features were delicate. Not yet a man. But no longer a boy.

To some people, such behavior and curiosities are abhorrent, wrong and unbiblical. Yet the courage of people like Bowie to bring those instincts to grace and acknowledgement have indeed changed the world, and for the better. The very idea that people all fall into plain and distinct categories is false and dangerous. It is the fascism of singularly self-directed purpose, and not godlike at all. Art, by contrast, explores the unspeakable. It sings it loud. Brings truth into the light.

Nature as well is both creative and forceful in its diversity. A society that collaborates with the forces of nature is a healthy one. The elements of the world that suppress and tries to murder the fact of diversity is one that fights against none other than itself. Men like Adolf Hitler, for example, made up their own version of reality. They try to cover their fears and insecurities with willful terror and murderous intent.

And that’s why David Bowie matters. His music and his leadership together changed the world. If anything, he battled a few s0-called demons in the process. But given the fact there are actually no such thing as real demons, he battled what the world threw at him instead. And in many respects, he won. And that’s the right kind of pride.

And that’s why David Bowie matters. His music and his leadership together changed the world. If anything, he battled a few s0-called demons in the process. But given the fact there are actually no such thing as real demons, he battled what the world threw at him instead. And in many respects, he won. And that’s the right kind of pride.

That’s the inspiration we can take from the passing of David Bowie. He forged a creative path that enabled him to overcome many fears about the world. He was born David Jones and chose his stage name from the inventor of a knife, it seems. Then he used it to cut both ways. There’s a powerful lesson in that.

A friend just texted me lyrics from the song Heroes. “We can beat them, forever and ever. We can be heroes, just for one day.” And that’s the best example of all. Thank you, David Bowie.

Before my late wife passed away, I sat down by her bed and told her that I loved her and asked forgiveness for any wrongs or ways that I might have disappointed her over the years. All relationships have some degree of failure in their mix. I thought it important to let her know how much I appreciated our time together, and to apologize for my own shortcomings. Her doctor had advised me to be absolutely positive in her last few weeks. Yet we’d been through quite a few things together, and I positively wanted to tell her how I really felt. That included a bit of confession. We all try our best, but love requires that we admit some of our shortcomings along the way.

Before my late wife passed away, I sat down by her bed and told her that I loved her and asked forgiveness for any wrongs or ways that I might have disappointed her over the years. All relationships have some degree of failure in their mix. I thought it important to let her know how much I appreciated our time together, and to apologize for my own shortcomings. Her doctor had advised me to be absolutely positive in her last few weeks. Yet we’d been through quite a few things together, and I positively wanted to tell her how I really felt. That included a bit of confession. We all try our best, but love requires that we admit some of our shortcomings along the way. Also, my companion Sue is respectful and loving toward our needs. Being a companion to a “widow,” as she has done, is not always easy. For both the spouse and the new companion, it can be difficult living in the shadow of someone so loved. Sue has treated my children with respect for their mother’s memory. She has grown to understand them better as people as a result, because learning about their mother has helped her understand their own characteristics and values. And in our relationship, I have been very honest with Sue about my feelings in the 2.5 years since my wife passed away.

Also, my companion Sue is respectful and loving toward our needs. Being a companion to a “widow,” as she has done, is not always easy. For both the spouse and the new companion, it can be difficult living in the shadow of someone so loved. Sue has treated my children with respect for their mother’s memory. She has grown to understand them better as people as a result, because learning about their mother has helped her understand their own characteristics and values. And in our relationship, I have been very honest with Sue about my feelings in the 2.5 years since my wife passed away. That is the protection. The risk is the investment in time and love we have made in each other. We have discussed the weight of that investment on several occasions. Dating in your 50s is not like dating in your 20s or 30s, when there are families to build and children on the horizon. Yet there is still an investment in the future. Even during the few years we’ve been together, we’ve felt changes in our bodies, hearts and minds.

That is the protection. The risk is the investment in time and love we have made in each other. We have discussed the weight of that investment on several occasions. Dating in your 50s is not like dating in your 20s or 30s, when there are families to build and children on the horizon. Yet there is still an investment in the future. Even during the few years we’ve been together, we’ve felt changes in our bodies, hearts and minds.

There were more than 2000 people milling around the start line of the Thanksgiving Turkey Trot in our hometown. My racing instincts from long ago sent me out to a quiet street for a one-mile warmup jog. It had already been an eventful week getting my house ready to host 12 people for Thanksgiving. I was looking for a place, I suppose, to take a deep, long breath before doing the race.

There were more than 2000 people milling around the start line of the Thanksgiving Turkey Trot in our hometown. My racing instincts from long ago sent me out to a quiet street for a one-mile warmup jog. It had already been an eventful week getting my house ready to host 12 people for Thanksgiving. I was looking for a place, I suppose, to take a deep, long breath before doing the race. All those years of caregiving for him were not quite over. There were still financial issues to manage, and the sale of his home to discuss. All that functions like a practical soliloquy that must be sung in order to gain closure.

All those years of caregiving for him were not quite over. There were still financial issues to manage, and the sale of his home to discuss. All that functions like a practical soliloquy that must be sung in order to gain closure. Not knowing what to expect after those quick changes, it struck me one day while walking into the home of my father that there were no real rules to this game. I was in charge of his life in consultation with my brothers. That meant there were always bills to pay and issues to discuss about his health and needs.

Not knowing what to expect after those quick changes, it struck me one day while walking into the home of my father that there were no real rules to this game. I was in charge of his life in consultation with my brothers. That meant there were always bills to pay and issues to discuss about his health and needs. There were many times I’d try to push the conversation toward something more pleasant such as memories of his that he might like to share. That was a tough gig too, because we could easily stall if I did not guess the name of the person involved in the story he wanted to relate. Even before his stroke we all had problems not knowing all the friends and family he thought we should know.

There were many times I’d try to push the conversation toward something more pleasant such as memories of his that he might like to share. That was a tough gig too, because we could easily stall if I did not guess the name of the person involved in the story he wanted to relate. Even before his stroke we all had problems not knowing all the friends and family he thought we should know. general that we, his sons, had never actually met. Or if we had, we did not remember them. Which was worse?

general that we, his sons, had never actually met. Or if we had, we did not remember them. Which was worse? This morning during my dog walk it was a bit surprising to find two yellow flowers blooming in the already pruned bed of a Master Gardener that lives nearby. She’s not one to pluck much of anything during the summer months. She prefers to leave her flowers out where everyone can admire them. But come autumn her garden beds get a full house-cleaning.

This morning during my dog walk it was a bit surprising to find two yellow flowers blooming in the already pruned bed of a Master Gardener that lives nearby. She’s not one to pluck much of anything during the summer months. She prefers to leave her flowers out where everyone can admire them. But come autumn her garden beds get a full house-cleaning.