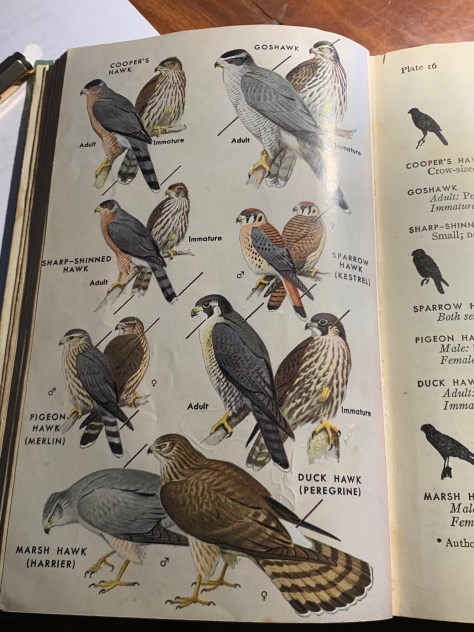

When I was five years old, my mother’s sister Carol handed me a copy of Peterson’s Field Guide to the Birds. Somehow she knew that I’d be interested in the subject. Over the years I purchased many other field guides that improved on the methods of the original book developed by Roger Tory Peterson. Yet I owe a sentimental debt to that first copy. It fueled my interest and taught me so much about the natural world.

With an early passion for drawing, I began tracing the birds in the Peterson’s Field Guide with a special focus on the hawks, which drew my attention the most.

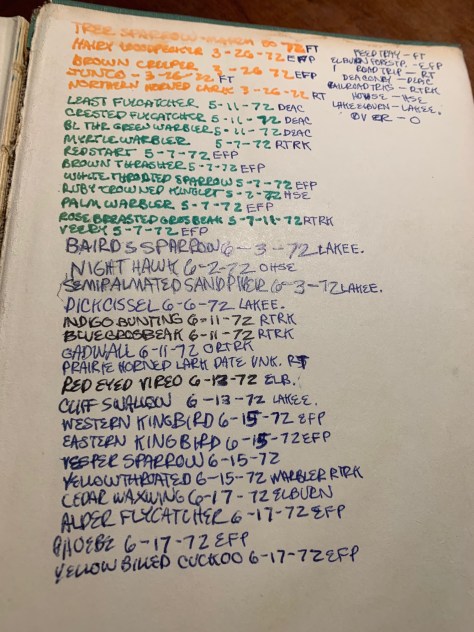

By the time I was twelve years old I was painting and drawing birds on my own. And when my eldest brother came home from college on fire with interest in birds after taking an ornithology course, we all went out in the field together to identify every bird we could find. These I marked down with eagerness and pride.

Among my friends, the interest in birds was at that age a point of teasing and ridicule. The nickname “Birdman” was applied with some disdain. But I ignored those supposed insults and kept painting and drawing birds because frankly, I was by then making some money at it.

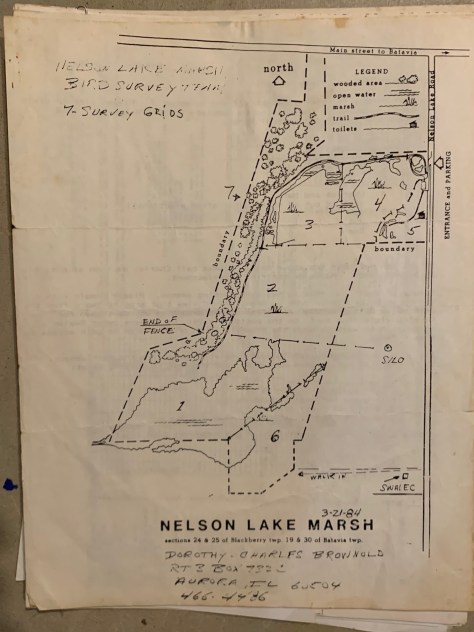

Through high school, I found a mentor in Robert Horlock, a biology teacher with whom I spent hours in the field. He introduced me to other birders. That led to my first engagement with Citizen Science as a founding member of the Nelson Lake Marsh Bird Survey team that tracked breeding and migratory species in a newly established wetland preserve. We participated in annual Audubon Christmas Bird Counts as well, a commitment that lasted for thirty consecutive years.

That bird survey team was one of the first times in my life that a seemingly childish interest felt validated in the adult world. My ability to credibly identify birds was respected by the adults with whom I met on a quarterly basis. My trips afield for that purpose felt serious and important. I was contributing to the preservation and conservation of something that I really loved. And having fun doing it. That was the right kind of pride, I thought.

Admittedly there was some ego involved in all my birding and art pursuits. As a young man with a strong need for approval, the praise earned for finding bids and doing artwork was a prized reward. So were the bragging rights in having seen twenty species of warblers on a cool spring morning, or calling in a peregrine falcon to the Rare Bird Alert phone line that served as the Internet for birders before the digital revolution began.

The thrills of birding over the years have included rare species that turned up at odd times. I wrote an article published in Bird Watcher’s Digest last year documenting the day that I found a European Stonechat in Illinois. It was the first of its kind seen in the Lower 48 United States. Lacking a camera on-site at the moment––it was before the era of cell phone cameras––I rushed home to do a painting and share it online. But unfortunately, the sighting could not be officially recognized by the Illinois Ornithological Union or any other organization because the bird was never viewed by another credible birder. Those are the rules. So the thrill of finding such a rarity remains a pleasure of my own accord.

These days I am well-equipped to document everything found in the field. Perhaps my obsession is in compensation for the frustration of losing that sighting of the Stonechat to the ether of personal history. I geared up over the years with a high-quality spotting scope to which I attached a series of digital cameras to take pictures of birds. Finally, I purchased a 150mm-600mm Sigma camera lens to use with my Canon camera. It’s not top-end gear, but it is fun to capture images of the birds I’ve studied for so many years.

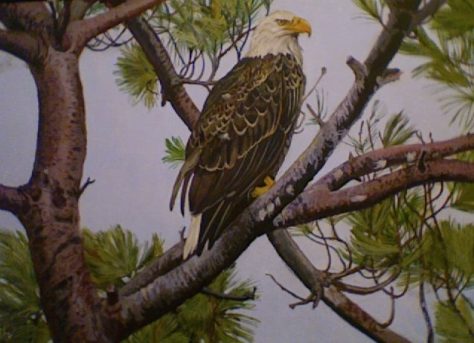

It would have been nice to have that kind of camera in my early years of birding when I tried so desperately to find “references” for my bird paintings. Back in the 70s and 80s when wildlife art was a big scene, it was artists with access to detailed photography that won the day. I tried to replicate that process over the years and finally produced some relatively solid work using my own photo references. But by then the market for bird paintings was waning. Digital photography now makes wildlife imagery so commonplace that entire sites on social media fill daily with photos of birds and other creatures. In many respects, the thrill that once came with celebrating those insights of nature is gone.

That said, my interest in birds has matured. My fascination now is with their behavior, and I still love leading people into the field to share in the thrill of seeing species of birds they never imagined existed. My personal life list of American species sits just below 500 and I’ll happily accept any new species that comes along. But that’s a rarity for sure these days unless I travel to a new place such as the Pacific Coast, where I hope to bird some day.

I’ll still paint birds and have a library of 20,000 images from which to work. It is a catalog of the time spent outside staring through optics and camera lenses at living things that deserve to be protected, celebrated and appreciated. I guess that’s enough approval for a bird nerd at last.

Christopher Cudworth is author of the book The Right Kind of Pride on Amazon.com.

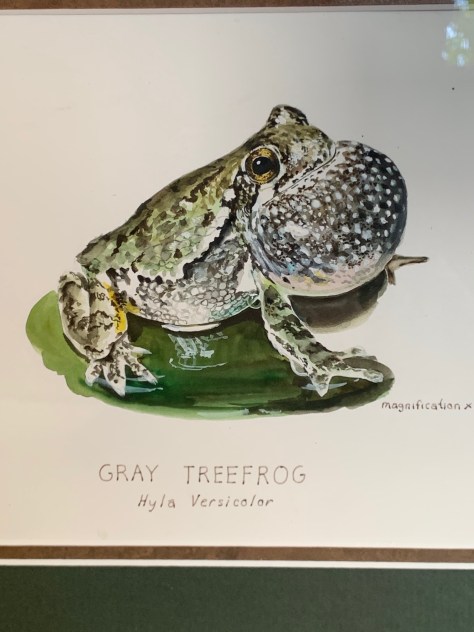

I don’t recall what motivated me to engage in this depth of depiction, but I can say that I was inspired by all the things we were studying. Part of our classwork involved capturing specimens of seven or eight different frog species. I got after it and found them all that spring. Then I set out to paint them in watercolor.

I don’t recall what motivated me to engage in this depth of depiction, but I can say that I was inspired by all the things we were studying. Part of our classwork involved capturing specimens of seven or eight different frog species. I got after it and found them all that spring. Then I set out to paint them in watercolor. Working from photographs I found in some book about frogs, I painted furiously over a period of two nights. The results were some of the most detailed illustrations I’d yet done in life. I was nineteen years old. And obsessed with real-life depictions.

Working from photographs I found in some book about frogs, I painted furiously over a period of two nights. The results were some of the most detailed illustrations I’d yet done in life. I was nineteen years old. And obsessed with real-life depictions. The spring peeper and gray treefrog illustrations were inspired by real-life encounters shining flashlights to find specimens on chill spring nights. We’d listened as well to the daytime calls of chorus frogs singing from flooded ditches. And toads whistling from dusk well into the night.

The spring peeper and gray treefrog illustrations were inspired by real-life encounters shining flashlights to find specimens on chill spring nights. We’d listened as well to the daytime calls of chorus frogs singing from flooded ditches. And toads whistling from dusk well into the night. But midway through the course, Dr. Roslien pulled me aside to let me know the truth about my future as a biologist. “I’ve not sure you’re a pure scientist,” I recall him sharing with me. “But you finish those six frog drawings and stuff those birds in that artsy way you do, and we’ll give you a B. But I’ve already talked to the Art Department. They’re eager to have you over there.”

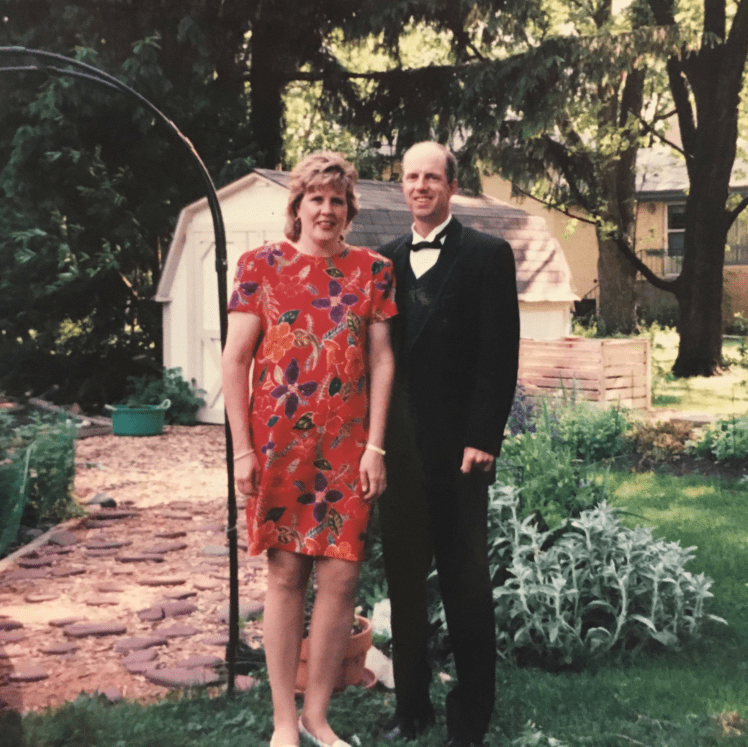

But midway through the course, Dr. Roslien pulled me aside to let me know the truth about my future as a biologist. “I’ve not sure you’re a pure scientist,” I recall him sharing with me. “But you finish those six frog drawings and stuff those birds in that artsy way you do, and we’ll give you a B. But I’ve already talked to the Art Department. They’re eager to have you over there.” During eight years of cancer caregiving for my late wife Linda, who passed away six years ago this day on March 26, 2013, I grew to understand many things about other people. How some have such a heart for others. How giving they could be. How friends willingly took on chores too difficult to imagine. All of it done without judgment. These things came true in our lives.

During eight years of cancer caregiving for my late wife Linda, who passed away six years ago this day on March 26, 2013, I grew to understand many things about other people. How some have such a heart for others. How giving they could be. How friends willingly took on chores too difficult to imagine. All of it done without judgment. These things came true in our lives. But it was stressful. Sometimes we’d be pressed financially, and it was on one of those nights that we added up the bills, said our prayer and got her into bed to rest.

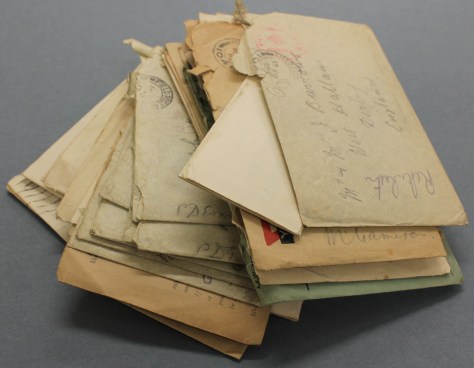

But it was stressful. Sometimes we’d be pressed financially, and it was on one of those nights that we added up the bills, said our prayer and got her into bed to rest. My brother recently found a treasure of letters sent to him over decades by our mother. He’s called me with insights about what she was thinking during different stages of her marriage to my father, which lasted more than fifty years.

My brother recently found a treasure of letters sent to him over decades by our mother. He’s called me with insights about what she was thinking during different stages of her marriage to my father, which lasted more than fifty years. Recently my son Evan drove west to California for a new venture in his career. On the way, he stopped by the South Rim of the Grand Canyon. Approaching the park, the snow was two feet deep, he informed us. He arrived in time to see the sun setting.

Recently my son Evan drove west to California for a new venture in his career. On the way, he stopped by the South Rim of the Grand Canyon. Approaching the park, the snow was two feet deep, he informed us. He arrived in time to see the sun setting.

So stop it. Make the ch-ch-ch-change in yourself when you speak of someone dying from cancer, or any other reason. They did not lose a battle against a disease or anything else. They won time to the best of their ability. And we should all honor that.

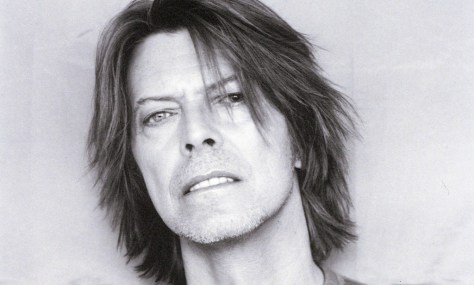

So stop it. Make the ch-ch-ch-change in yourself when you speak of someone dying from cancer, or any other reason. They did not lose a battle against a disease or anything else. They won time to the best of their ability. And we should all honor that. Bowie and I go back to the Ziggy Stardust album, which I revered as a sophomore in high school. The androgyny of the character and his person both fascinated and terrified me. At the time, it was not acceptable in any form to be considered feminine by those terms. Not in the tiny farm town where I lived.

Bowie and I go back to the Ziggy Stardust album, which I revered as a sophomore in high school. The androgyny of the character and his person both fascinated and terrified me. At the time, it was not acceptable in any form to be considered feminine by those terms. Not in the tiny farm town where I lived. And that’s why David Bowie matters. His music and his leadership together changed the world. If anything, he battled a few s0-called demons in the process. But given the fact there are actually no such thing as real demons, he battled what the world threw at him instead. And in many respects, he won. And that’s the right kind of pride.

And that’s why David Bowie matters. His music and his leadership together changed the world. If anything, he battled a few s0-called demons in the process. But given the fact there are actually no such thing as real demons, he battled what the world threw at him instead. And in many respects, he won. And that’s the right kind of pride.

Before my late wife passed away, I sat down by her bed and told her that I loved her and asked forgiveness for any wrongs or ways that I might have disappointed her over the years. All relationships have some degree of failure in their mix. I thought it important to let her know how much I appreciated our time together, and to apologize for my own shortcomings. Her doctor had advised me to be absolutely positive in her last few weeks. Yet we’d been through quite a few things together, and I positively wanted to tell her how I really felt. That included a bit of confession. We all try our best, but love requires that we admit some of our shortcomings along the way.

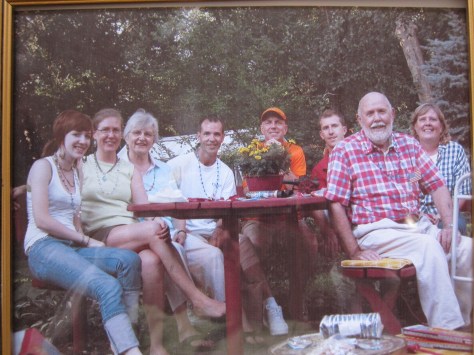

Before my late wife passed away, I sat down by her bed and told her that I loved her and asked forgiveness for any wrongs or ways that I might have disappointed her over the years. All relationships have some degree of failure in their mix. I thought it important to let her know how much I appreciated our time together, and to apologize for my own shortcomings. Her doctor had advised me to be absolutely positive in her last few weeks. Yet we’d been through quite a few things together, and I positively wanted to tell her how I really felt. That included a bit of confession. We all try our best, but love requires that we admit some of our shortcomings along the way. Also, my companion Sue is respectful and loving toward our needs. Being a companion to a “widow,” as she has done, is not always easy. For both the spouse and the new companion, it can be difficult living in the shadow of someone so loved. Sue has treated my children with respect for their mother’s memory. She has grown to understand them better as people as a result, because learning about their mother has helped her understand their own characteristics and values. And in our relationship, I have been very honest with Sue about my feelings in the 2.5 years since my wife passed away.

Also, my companion Sue is respectful and loving toward our needs. Being a companion to a “widow,” as she has done, is not always easy. For both the spouse and the new companion, it can be difficult living in the shadow of someone so loved. Sue has treated my children with respect for their mother’s memory. She has grown to understand them better as people as a result, because learning about their mother has helped her understand their own characteristics and values. And in our relationship, I have been very honest with Sue about my feelings in the 2.5 years since my wife passed away. That is the protection. The risk is the investment in time and love we have made in each other. We have discussed the weight of that investment on several occasions. Dating in your 50s is not like dating in your 20s or 30s, when there are families to build and children on the horizon. Yet there is still an investment in the future. Even during the few years we’ve been together, we’ve felt changes in our bodies, hearts and minds.

That is the protection. The risk is the investment in time and love we have made in each other. We have discussed the weight of that investment on several occasions. Dating in your 50s is not like dating in your 20s or 30s, when there are families to build and children on the horizon. Yet there is still an investment in the future. Even during the few years we’ve been together, we’ve felt changes in our bodies, hearts and minds.

There were more than 2000 people milling around the start line of the Thanksgiving Turkey Trot in our hometown. My racing instincts from long ago sent me out to a quiet street for a one-mile warmup jog. It had already been an eventful week getting my house ready to host 12 people for Thanksgiving. I was looking for a place, I suppose, to take a deep, long breath before doing the race.

There were more than 2000 people milling around the start line of the Thanksgiving Turkey Trot in our hometown. My racing instincts from long ago sent me out to a quiet street for a one-mile warmup jog. It had already been an eventful week getting my house ready to host 12 people for Thanksgiving. I was looking for a place, I suppose, to take a deep, long breath before doing the race. All those years of caregiving for him were not quite over. There were still financial issues to manage, and the sale of his home to discuss. All that functions like a practical soliloquy that must be sung in order to gain closure.

All those years of caregiving for him were not quite over. There were still financial issues to manage, and the sale of his home to discuss. All that functions like a practical soliloquy that must be sung in order to gain closure. Not knowing what to expect after those quick changes, it struck me one day while walking into the home of my father that there were no real rules to this game. I was in charge of his life in consultation with my brothers. That meant there were always bills to pay and issues to discuss about his health and needs.

Not knowing what to expect after those quick changes, it struck me one day while walking into the home of my father that there were no real rules to this game. I was in charge of his life in consultation with my brothers. That meant there were always bills to pay and issues to discuss about his health and needs. There were many times I’d try to push the conversation toward something more pleasant such as memories of his that he might like to share. That was a tough gig too, because we could easily stall if I did not guess the name of the person involved in the story he wanted to relate. Even before his stroke we all had problems not knowing all the friends and family he thought we should know.

There were many times I’d try to push the conversation toward something more pleasant such as memories of his that he might like to share. That was a tough gig too, because we could easily stall if I did not guess the name of the person involved in the story he wanted to relate. Even before his stroke we all had problems not knowing all the friends and family he thought we should know. general that we, his sons, had never actually met. Or if we had, we did not remember them. Which was worse?

general that we, his sons, had never actually met. Or if we had, we did not remember them. Which was worse?