In late 2012, just a few months before my late wife passed away, she attended a preschool conference presented by an insightful man talking about the effects of attention deficit disorder, or ADD. She came home that day and told me flat out: “This is you.” To her credit, she was offering the advice of a hard-headed woman. We all need that.

While the signs were all around us, we’d never talked about the subject of my occasional and sometimes persistent attention deficit disorder. Up to that point in life, I’d concentrated on coping with the effects of anxiety in my life. I’d been an anxious nailbiter since birth, a condition exacerbated by childhood trauma centered around physical and verbal abuse in the family. In an echo of that youth, I woke up pounding my pillow in anger at the age of twenty-nine.

By that point, I was taking steps to become mentally healthy after muddling through my twenties after a couple of years running full-time in a journeyman’s address of unfinished business. For me, running became the best form of therapy for anxiety and depression. Yet I ultimately needed to back away from the fact that it also ruled my life. I ended my competitive running career at the age of twenty-seven after getting married and conceiving our first child. I’ve always thought that was a mature step to take. I still do.

I still needed to assuage some of the anger resulting from life’s earlier experiences. By my early thirties, I’d sought therapy a few times without any grand results. One psychologist told me that I just needed to be stronger for my wife, and that would cure things. Sometimes we get shitty advice at the worst times in life.

On my own accord, I’d left a messed up job at the terminally corrupt Boy Scouts of America. From there I worked first in sales and then twenty-plus years in marketing with long streaks of career success interrupted by emphatic blunders. Those resulted from my lack of executive function as well as a propensity to talk too much in business situations and uncomfortably overshare because a mind consumed by ADHD unwittingly desires such things. I take responsibility for it all.

By the time 2005 rolled around, I was working as a marketing manager for the third-largest newspaper in Illinois. I’d built a burgeoning literacy program in collaboration with more than one hundred seventy public libraries serving 375,000 families. That same year, my mother passed away from pancreatic. Instantly, I became a caregiver to both my wife with ovarian cancer, and my father, who’d been a stroke victim since 2003.

Ironically, I thrived on the focus and pressure of caregiving. Little phased me in dealing with medical emergencies or day-to-day needs. Like most competitive distance runners, I thrived on challenges. That’s the stuff I could handle because ADHD actually embraces those functions. I had no problem turning my attention to what my wife or father needed. Hyperfocus is the superpower of ADHD.

It was always boredom that I dreaded. Quiet moments with nothing going on. God Forbid. That’s why I eventually took up cycling to complement the running. And later on, even swimming. Because moving is my salvation from inattention. It calms my brain. Allows me to think. I solve problems and come home ready to deal with reality. Boom.

Then there was the writing and the art. For those eight years with my late wife going in and out of remission, dealing with countless chemotherapy sessions and surgeries to boot, I’d sit my ass down and write my way through the stress. Or paint. The blogs I wrote to all the people supporting us through a caregiving website became the book I wrote about that journey. I titled it The Right Kind of Pride, pointing to vulnerability as the best kind of honesty and virtue.

As things wound down in 2012 and my wife struggled with seizures caused by cancer that had moved to her brain, she kept on teaching at the preschool where she worked. That was her salvation. Keep on keeping on. Yet after brain surgery and intense radiation treatments in early 2013, she needed steroids to cope with the bodily inflammation. Hyped up on powerful drugs, her personality went off the register and she lost functional capabilities and judgment. The preschool teaching had to end.

Yet before that period when her own health and mental state were fragile, she’d taken a cool look at my version of reality and shared that she’d seen enough in that presentation on ADD to know that I was definitely on that spectrum. All those years of lost keys and forgotten appointments, unfinished projects or commitments not quite fulfilled had taught her that I was possessed of a type of mental illness that didn’t just “go away” on its own.

I needed help. Yet for all her prescience, it would still take a few years to act on her wisdom.

Sometimes help comes in tangents, not in straight lines. During a therapy session with a counselor from Living Well Cancer Resource Center, the psychologist noted that I’d done well for years working with my demanding father despite age-old differences and emotional conflicts. “You seem good at forgiving others,” she observed. “How are you at forgiving yourself?”

That was an eye-opening observation. From that point on I was less harsh on myself for emotional failings and/or taking blame for familial disagreements. I’d stayed strong for my dad and my wife all those years despite many career and financial challenges along the way. I’d stayed the course. Forgiven what was needed to move on. We all do our best. That hasn’t resolved all the issues of course. Life is always a work in progress.

The big issue left to resolve was how to work with how my brain actually works. After all, I’d managed to produce plenty in life. Solo art shows. Written books and published limited edition prints. Placed articles in national magazines. That shit wasn’t all bad!

Yet it wasn’t until recently when my son Evan raised the issue of ADHD in our lives that I fully accepted the impact it has had on us. Looking back, I recall teacher conferences in which my mother (herself a teacher) met with instructors to discuss my lack of attention in class. Later on, through high school, I nearly failed subjects such as algebra if they disinterested me. Yet I got A’s in subjects I liked. I made it through college with a 3.1 average out of 4.0 but suffered some bad grades along the way. That’s life with ADHD. You can do nine out of ten things well, but the tenth one will bite you in the ass.

To this day, I realize that ADHD impinges on my ability to grasp certain kinds of material. That has cost me jobs, money, and even relationships. While I pride myself on paying attention to friends and family, sometimes I miss what people really want from me. There is considerable pain that comes with that gap in action and understanding.

Coming to grips with the impact of ADHD is not an easy thing. While forgiving yourself is a direct process, and dealing with the inevitable outcomes of an inherent mental condition is vital, seeking forgiveness from others isn’t an easy task. All we can do is keep trying.

In the meantime, I pat my pockets whenever I go out the door. To that end, I am vigilant about ADHD. I also remarried and my wife Sue looks at me differently than anyone I’ve ever known. An occasional “forget” is no big deal to her. Lacking that pressure, I seem to forget less than ever as a result. A hard-headed woman is a good thing to find. I’ve been blessed in life with a couple of them.

I first purchased a James Taylor album as a freshman in high school along with works by Paul Simon, Neil Young, David Bowie, Bob Dylan, and Elton John, to name a few. Among those, there were a few mentions of God in the lyrics, a subject of consequence since I’d recently chosen on my own to get confirmed along with friends at the church whose pastor lived right next door to me.

I first purchased a James Taylor album as a freshman in high school along with works by Paul Simon, Neil Young, David Bowie, Bob Dylan, and Elton John, to name a few. Among those, there were a few mentions of God in the lyrics, a subject of consequence since I’d recently chosen on my own to get confirmed along with friends at the church whose pastor lived right next door to me.

The choice to move from my home of twenty years was not an easy decision to make. It was the childhood home of my children, and a healthy degree of sentiment was attached to the place as a result. It was also the home where my late wife and I spent so many years, and she passed away within its walls.

The choice to move from my home of twenty years was not an easy decision to make. It was the childhood home of my children, and a healthy degree of sentiment was attached to the place as a result. It was also the home where my late wife and I spent so many years, and she passed away within its walls.

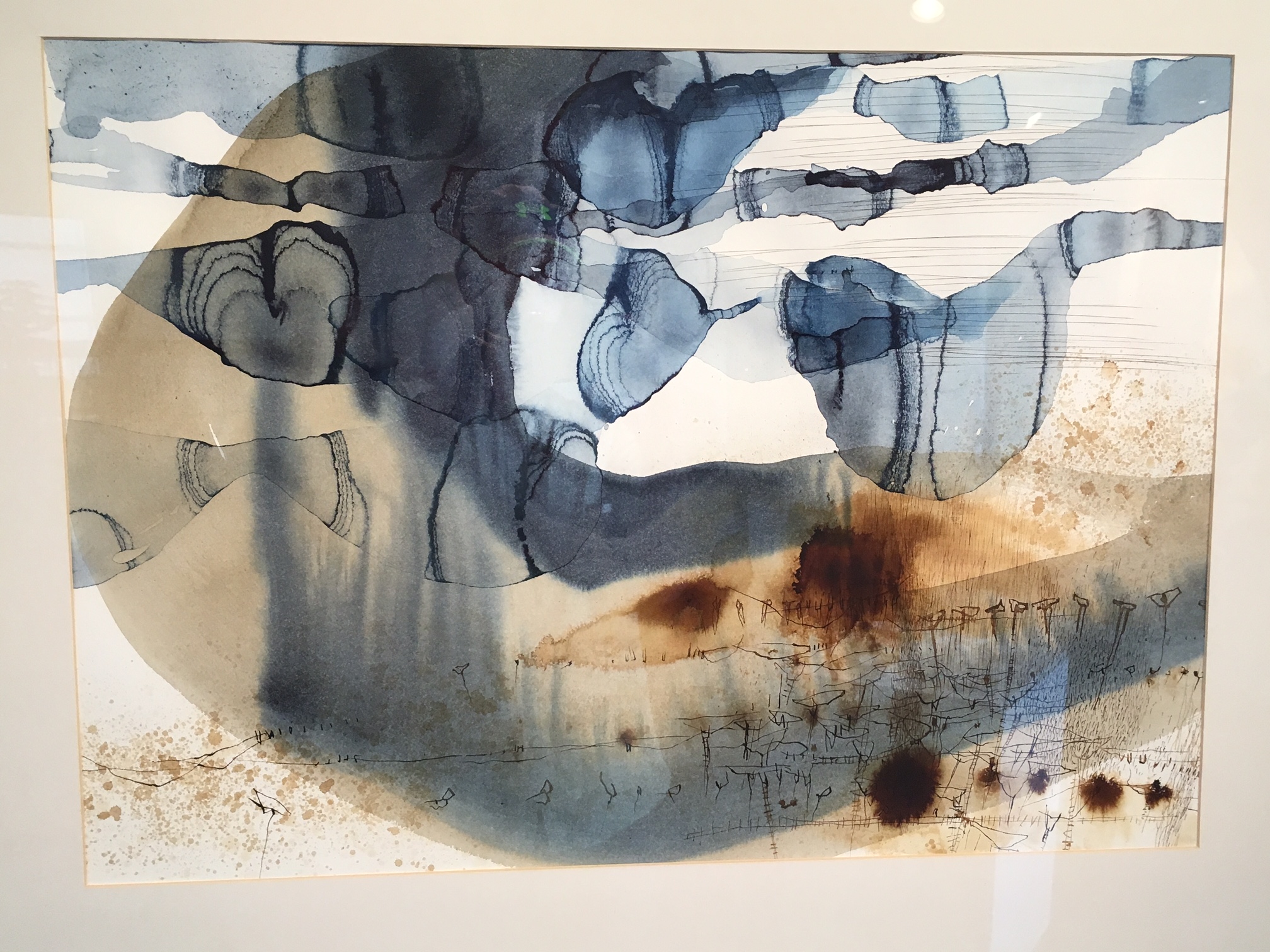

Occasionally I see the work of another artist and feel compelled to tell the world about it. And while Ana Zanic of Geneva is doing quite well for herself with paintings now featured in shows that include galleries in Chicago, New York, Denver and Baton Rouge, that does not mean one cannot add to the discussion.

Occasionally I see the work of another artist and feel compelled to tell the world about it. And while Ana Zanic of Geneva is doing quite well for herself with paintings now featured in shows that include galleries in Chicago, New York, Denver and Baton Rouge, that does not mean one cannot add to the discussion. Suggestively, these same shapes could well be the processes that invented and expanded the universe, and from within these massive forms come Zanic’s textural commentaries. Tiny drawn figures seem to vacillate between material forms and energy. Sometimes they appear to be forests emerging from the earth. At other times, they seem to convey a population of thoughts or recollections. This is what makes her work so pleasing, accessible and yet mysterious at the same time. To complete this journey from thought to form, she has also created a series of pottery pieces that bear the same conversational inscriptions.

Suggestively, these same shapes could well be the processes that invented and expanded the universe, and from within these massive forms come Zanic’s textural commentaries. Tiny drawn figures seem to vacillate between material forms and energy. Sometimes they appear to be forests emerging from the earth. At other times, they seem to convey a population of thoughts or recollections. This is what makes her work so pleasing, accessible and yet mysterious at the same time. To complete this journey from thought to form, she has also created a series of pottery pieces that bear the same conversational inscriptions. It is high time that all of us come to grips with the fact that the world is not a “paint by number” place. Physics and evolution demand that knowledge. We also now know there is space between all matter, and dark matter beyond that. We even have the ability to shoot neutrinos through the earth. As it turns out, the pigment of our vision exists as much by force of imagination as it does in reality.

It is high time that all of us come to grips with the fact that the world is not a “paint by number” place. Physics and evolution demand that knowledge. We also now know there is space between all matter, and dark matter beyond that. We even have the ability to shoot neutrinos through the earth. As it turns out, the pigment of our vision exists as much by force of imagination as it does in reality.