In the late spring of 1970, the Cudworth family unrooted itself after seven years in Lancaster, Pennsylvania and moved 750 miles west to the small town of Elburn, Illinois. My father was laid off from work at RCA back east and landed a job with a company called National Electronics (now Richardson Electronics between Elburn and Geneva) as a sales engineer.

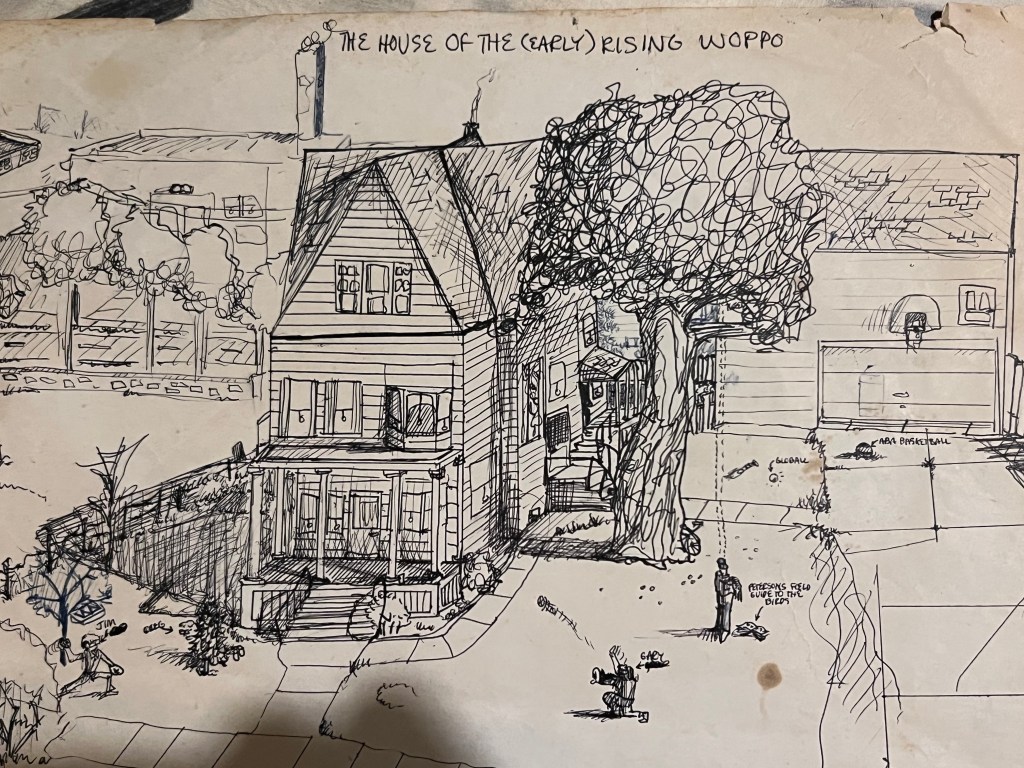

For me, moving that far west meant leaving close friends behind back in Pennsylvania. The only thing that made the move enticing for me at the age of twelve was a Polaroid photo of a basketball backboard with a square behind the rim that my father sent back to show us what our new home would look like. As a kid deeply into basketball at the time, and caught up in the “new look” of the game with squares at which to aim a bank shot, that single photo made it seem partially worthwhile to deal with such a big change in life.

New friends

That still left it for me to make new friends in a small town situated on the railroad tracks forty miles west of Chicago. Fortunately, news got around town that I could dribble and shoot a basketball like it was magic, and I met a couple of guys named Mark Strong and Eric Berry.

Within weeks we began hanging out and doing what twelve-year-olds going on thirteen typically do. We played sports and tried to get the attention of girls that lived in town. There were always older guys around with their cars and muscles and cool haircuts, especially in the summertime. The girls were most interested in them, but we still got to hang around with a couple of girls named Allison and Twyla. Both had the last name Anderson.

These were my “new friends” in Illinois.

Nicknames and other games

That summer I went out for baseball as I’d done back east where the team I’d joined won the prestigious Lancaster New Era Championship. We were schooled in fundamentals and played at the highest level for our age. But the first team they put me on in Elburn at 12 years old was a town team for 8-12 year olds. I threw a perfect game and the coaches all gathered ’round and told me that I’d have to move up to the American Legion team for sixteen-year-olds and above.

That set the stage for playing Elburn baseball the next few summers, and my new friend Mark Strong played on that team along with some guys I’d met through school. Our friend Eric Berry wasn’t that interested in baseball, so our friendship ebbed and flowed with the seasons. Yet we still got together to ride bikes around the small streets until well after dark. We’d get bored now and then and with my baseball pitching skills I grew adept at breaking streetlights with roadside rocks. It was small-town entertainment at its “best.” Not.

During the summer months, Mark and I often headed out to the fields beyond the east edge of Elburn where giant ponds filled the clay holes where topsoil had been graded off to prepare for new homes. We’d play army in the dirt or blow up frogs with firecrackers. In winter, Mark and I took his shotgun out for sport. Even though I’d become a birdwatcher by the age of thirteen, I’ll confess to shooting a few sparrows with his 12-gauge. They mostly disappeared.

One early winter day we used our BB guns to peg house sparrows off a large bird house behind his home. What we thought were echoes from our BBs striking the bird house turned out to be a ton of holes in the neighbor’s large glass window. Yes, we had to pay for the damages.

For all our juvenile delinquent instincts, we also served as the town’s paperboy service for several years. Mark and Eric (better known as Eeker, his nickname) owned the route first. They handed the route off to me when I was a freshman in high school. The route paid about $8.50 per week, enough to keep me in candy bars and cinnamon rolls at Kaneland High School. I’d collect the papers at Smith’s Bar-B-Cue in downtown Elburn and deliver them inside the doors of the thirty or so homes on the route.

Competitive natures

For all our friendship endeavors, Mark and I were immensely competitive with each other. We played sports all the time. As luck had it, Mark’s father was the elementary school principal in town. That gave us access to the school gym. On cold winter days we’d head to the school to play basketball or try to beat each other in a game we invented, call it Wall Ball. We used one or two of those ugly red recess balls with the seashell patterns on them. The game had simple rules. You could throw the ball from up to half court and the object was to hit the far wall below a tile line without letting the other guy block it. That was worth one point. Hitting the basketball backboard was two points and actually shooting a basket was worth a whole five points. In the heat of that game, we sank more shots than you might think. We’d play Wall Ball for an hour or more sometimes.

Once we got into high school, Saturdays were when Mark played football for Kaneland High School and I ran cross country. After that, we’d meet up at his house for even more sports stuff. My legs would be sore and tired from racing three miles, and Mark was bruised from football, but we’d take turns playing receiver while his dad played quarterback. Mark was bigger and stronger than me, but not as adept or quick. All told, our games were typically even. Yet I remember a day when I got the best of him for one reason or another and as I left to go home I could hear his father counseling him on not giving up.

Neither Mark or I were the type to quit anything easily. But life has a way of sorting things out no matter how determined you might be to do something. As an 8th grader, I’d won the town Punt, Pass, and Kick contest, advancing to regionals. Part of me apparently thought that throwing and kicking the ball was what football was all about. My father knew better and never let any of his four boys go out for football. He’d seen what it did to his high school and college friends who came away with busted up knees and shoulders. On the day that I was ready to sign up for football my freshman year, my father grabbed me by the scruff of the neck at the locker room door and said, “You’re going out for cross country, and if you come back out of that locker room, I’ll break your neck.” My dad was right. I made the Varsity as a freshman and would likely have been crushed in football. I weighed 128 lbs.

So it was football for Mark and cross country for me. Our mutual friend Eeker drifted into the arts and theater, interests that matched his musical talent. His brothers all played instruments and they’d rehearse playing CS&N and Beatles tunes in the upstairs of the local Catholic Church. The Berry’s were one of the wealthier families in town. Their dad Ed Berry would eventually become mayor.

Eric and I did cross sporting paths in track, where he excelled in pole vault like his brothers Mark and Chris. The Berry boys all had a wild streak and vaulting paralleled their love of thrills that included downhill skiing in the winter months. I also accompanied the Berry Boys in some late-night thievery as they had set their eyes on some fat tire slicks on a vehicle downtown. I never had any instinct for motor sports and didn’t see the thrill in doing “burnouts” in a car, but I crept around to help them get the prized slicks off the jacked-up car. The closest I ever came to laying rubber was making skid marks with my Huffy three-speed bike.

For all our hijinks, there was a moral side to Mark and I as well. We both joined the confirmation class at the downtown church pastored by Rev. Wilhite, who was also my next-door neighbor. Our confirmation class discussions covered everything from the radical scope of the new musical Jesus Christ Superstar to what it means to believe in God. Reverend Wilhite was an able guide as he spoke to church doctrine while remaining open-minded to the coarse speculations of young minds.

My parents attended a church in Geneva but I had decided on my own to get confirmed at that little church in Elburn. I wasn’t alone in that. Many friends from Elburn and Kaneland Junior High joined us in that naive but earnest effort to commit ourselves to faith in some way.

A social kid

Mark and I remained friends into our high school years but being in different sports did drift us apart a bit. Plus, the social system at Kaneland was often harsh and involved a ton of hard teasing and worse. I remember times when our peers mocked both Mark and I for various reasons. They gave him the nickname Roy, which wasn’t a compliment. My nickname was Woppo based on a mistake I’d made in some half-assed art class where I wrote my name Cudwopth rather than Cudworth. First came Cudwop, then Woppo. Mostly it was a term of endearment, but always with a tone of snark to it. I was a popular kid yet still a dopamine-driven dreamer with a lack of self-esteem. A classmate once walked up to me during a track meet and muttered, “Cudworth, you’re just a hayseed.” Honestly, that was pretty accurate. I was a child of the outdoor margins, happiest when trouncing about in the Elburn Forest Preserve finding new bird species.

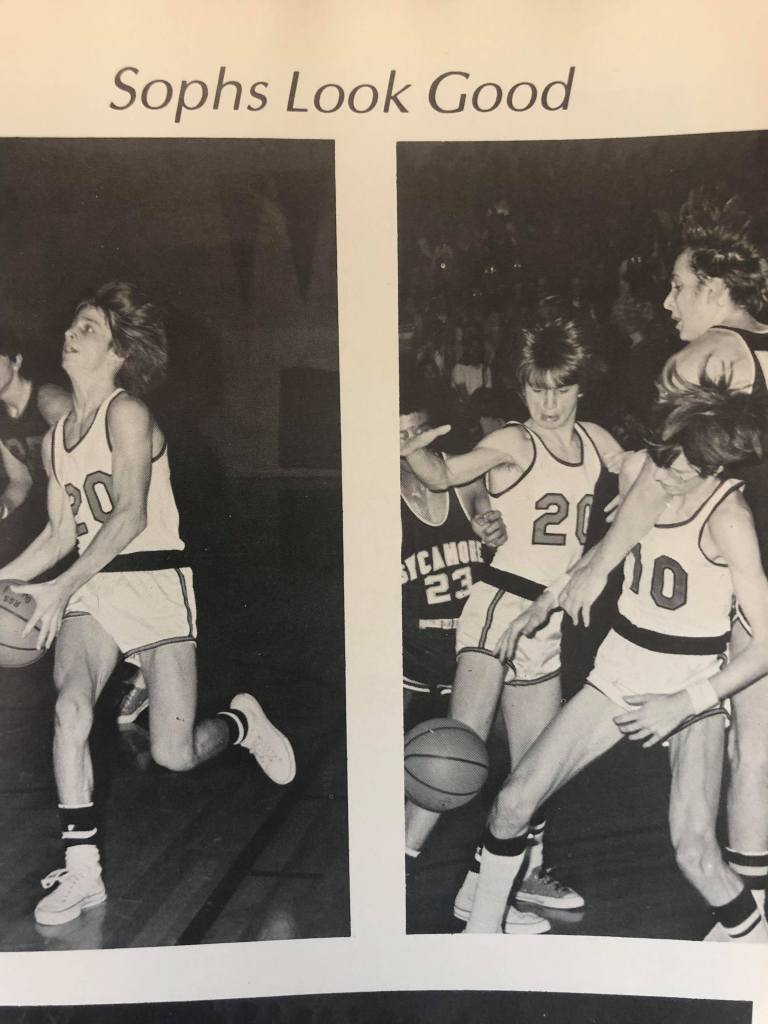

But I always came back to the realm of sports, and during the winter months that meant hours playing basketball in one sphere or another. My homework suffered and my Converse shoes wore holes in the bottom. More than one set of glasses met an awful end thanks to the elbows thrown in basketball. That’s me, #10 in the photo below.

I don’t recall if Mark went out for wrestling but that would not have surprised me. He was a tough-minded guy in many respects. In classic guy fashion, had quite a protracted arguments on subjects such as whether basketball or football players were better all-around athletes. Mark said football. I said basketball of course. I was loyal to the game because I was decent at it. It gave me self-esteem as even older kids invited me to play games at Morris’s barn, an actual farm structure with a b-ball court in the upstairs.

By the time I was a sophomore I’d become class president as a somewhat popular kid. I didn’t know a damned thing about what I was supposed to do in that role other than choose the class ring. That was one of many moments in life when I accepted a job without a clue about what it involved.

An ordered mind

Mark was a direct contrast to that approach. I seem to recall him working a summer job inseminating cows at a big facility north of Elburn. He described the work of plugging cows with semen packs and I almost puked thinking about it. The truth is that Mark had a pragmatic streak that bordered on stubborn. He didn’t blanch at hard work or being honest. For that attribute he became the butt of teasing at school as I recall. I may have joined in on some of that too. We all did.

Kaneland (like so many high schools) was at times a cesspool of ridicule. There are always smart people in every social circle who engage in dumb rituals by making fun of others. We’re seeing it in spades in the United States these days. The habit of mocking or ostracizing people to gain social or political advantage is common in American society. Anyone who strays from the “straight and ordinary,” or thinks or acts differently is open season. When those belief systems become institutionalized in any way it can tip whole societies.

Those of us trying to buck those trends at any scale find it hard to swim upstream. I got mocked for my birdwatching during high school. Even as a successful athlete I got manipulated by guys with less talent to stop believing in myself. People often tried to bring you down a rung or use some social cue to make you feel inferior. I even recall have female friends that I trusted and being told they weren’t worth it if I wasn’t somehow trying to get something from them or “hustling them.”

As a person eager for approval, I might have fallen prey to some of those pressures had our family stayed in Elburn. That wasn’t to be.

Moving on, moving out

In the middle of my sophomore year my father announced that we were moving from our big home next to the “deaconry” in Elburn to a little house in St. Charles. I was torn in two by the decision because I’d worked hard to make good friends at Kaneland, yet at the same time sensed there was always opportunity for change.

Rumors floated that I was “recruited” to St. Charles by the track and cross country coach Trent Richards, a Kaneland graduate that had coached me in Elburn baseball. Frankly, I wasn’t that great of a runner to be the subject of recruiting or any other tactic. I was just a kid who could run decently trying my best to make a place in the world.

The process of leaving Kaneland for a nearby school was awkward at best. Some of my classmates thought I was doing it on purpose, but the facts were different. I never had any say in the matter. Twenty-five years later, my father told me that we left Kaneland so that my younger brother (6’6″) would not have to play basketball for the slowdown offense at Kaneland. As it turned out, my dad made a good decision. My brother earned All-State Honorable Mention at St. Charles and earned a D1 scholarship.

When my father told me why we moved, I replied, “What about me?”

“I knew you were a social kid,” he responded. “I knew you’d get along.”

No goodbyes

I don’t recall saying goodbye to either Mark Strong or Eric Berry when we moved or as some painful goodbye after the last day of school at Kaneland. That day was anticlimactic, as I recall. My dad picked me up after the last day of classes and we drove away on a warm spring day.

After that I lost touch with most folks at Kaneland except when my buddies at St. Charles wanted to meet the pretty Kaneland girls. I told them, “Look, I didn’t have an inside track when I went there. What makes you think I could do any better now?”

As an athlete in St. Charles, I’d wind up competing against Kaneland in cross country, basketball and track. I was admittedly jealous when the Kaneland track team won the state championship during our senior year. On that front I wondered what it might have been like to stay at that school. Would I have been better or worse off?

A partial answer to that question came weeks after the last day of high school. My “former friend” Mark Strong called me one day and said, “Come on. Let’s go to a party they’re having outside of town. I have some new music for you to hear.”

We piled into Mark’s car. It was good to see him again. He turned the key and started the engine. Then he popped a tape into the deck and started blasting Bruce Springsteen’s new album, Born to Run.

In the day we sweat it out on the streets

Of a runaway American dream

At night we ride through the mansions of glory

In suicide machines

Sprung from cages on Highway 9

Chrome wheeled, fuel injected, and steppin’ out over the line

Oh, baby this town rips the bones from your back

It’s a death trap, it’s a suicide rap

We gotta get out while we’re young

‘Cause tramps like us, baby, we were born to run

Yes, girl, we were

Mark looked over at me and smiled. “I knew you’d like this…”

I had not yet heard of Springsteen. Then he played some new Supertramp from Crime of the Century. The lyrics in the middle of song nearly knocked me out.

Write your problems down in detail

And take ’em to a higher place

You’ve had your cry, no, I shouldn’t say wail

In the meantime hush your face

Right (quite right), you’re bloody well right

You got a bloody right to say

It felt good to connect with him again. But later at the party we got separated and I was left to wander a backyard bash rife with all kinds of drugs and booze. I was now completely out of my league. The most I’d ever done in high school was drink a few beers. I saw people on speed and pot, drugs that were completely unfamiliar to me. I don’t remember how I got back home that night. Perhaps I found Mark and he drove me to St. Charles. I was relieved. Not saying that I blame Mark for that experience. Quite the opposite. In many respects if was revelatory. I’d learned all I needed to know about the previous two years. I think he was trying to tell me, in some ways, that he was a survivor.

Perhaps it was our mutual experiences dabbling in Christian thinking when we were just 8th graders. Or maybe it was just riding our bikes on quiet streets in downtown Elburn with the stench of the meat packing plant filling our noses that taught us the world could be a stinking place to be. I know now that Mark went on to some challenges in school and such, just as I had done. But he emerged a thinking man and these days, as we recently shared over coffee, he’s a man of strong faith and in eager pursuit of truth related to his religion.

The Sodom Dig

So we caught up recently and I learned that Mark has spent the last several years as an active archeologist working a dig that is suspected to be the city of Sodom, famous in the Bible for its destruction by some cataclysmic event. The dig is ongoing and was the subject of an article in Nature magazine. This is one of those cases where science converges with religion and people are trying to figure out what it all means.

Mark shared one fascinating perspective with me about the findings there and other archeological work in Jordan and other Middle East locations. “We’ve disproven the lineage of Adam through Jesus,” he wryly noted.

“Whoa,” I replied.

“Yeah,” he chuckled.

This is the aspect of Mark Strong that I find most interesting. He unrelentingly follows what the information tells him. Yet he’s also a saved, born-again Christian. In other words, he’s exactly the kind of Christian this world needs if it’s going to be honest about the tradition, history and truth of scripture and everything after.

That’s interesting because while I approach scripture more from the aspect of what I call “outcomes” related to religion and history, science and politics, we have engaged in what one might call “convergent evolution” when it comes to our respective beliefs. Mark is clearly a bit more “conservative” in some aspects of his worldview. I am certainly more “liberal” in my outlook, believing that Christian tradition has gotten many things wrong over the years. But look at us now. We’re still capable of having the same kind of healthily competitive relationship that we did fifty years ago.

We’ll meet again sometime soon. Because while we laughed at some old stories, our worlds now convene very much in the present. He said a prayer for me before we left. I was graced by that action and don’t take such sincerity lightly. That is the right kind of pride, to care and be cared for. We should all be so lucky to cycle through life with that in mind.

I first purchased a James Taylor album as a freshman in high school along with works by Paul Simon, Neil Young, David Bowie, Bob Dylan, and Elton John, to name a few. Among those, there were a few mentions of God in the lyrics, a subject of consequence since I’d recently chosen on my own to get confirmed along with friends at the church whose pastor lived right next door to me.

I first purchased a James Taylor album as a freshman in high school along with works by Paul Simon, Neil Young, David Bowie, Bob Dylan, and Elton John, to name a few. Among those, there were a few mentions of God in the lyrics, a subject of consequence since I’d recently chosen on my own to get confirmed along with friends at the church whose pastor lived right next door to me.