For the last few years, I’ve been substitute teaching in four different public school districts in our area. I attended school in two of them, Kaneland from 8th through 10th grade, and St. Charles from Junior to Senior year.

That all came about from having transferred from one district to another during my sophomore year in high school. That wasn’t fun or easy, but I made it work thanks to my interest in sports and general ease in making friends. Twenty-five years after those events, I asked my father why we moved. I said “Dad, I was the top runner and Class President at the Kaneland.” But he told me, “I didn’t want your younger brother to play basketball in that slowdown offense at Kaneland.”

“What about me?” I replied.

“I knew you were a social kid,” he smiled. “I knew you’d survive.”

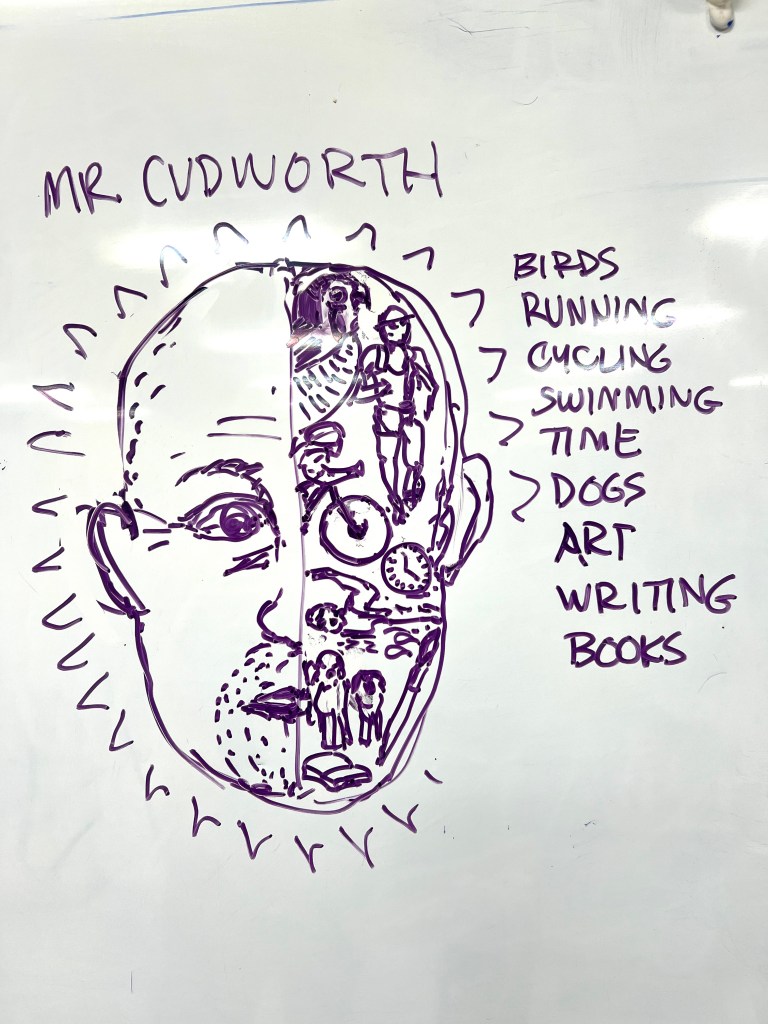

He was right. Thanks to cross country, basketball and track, plus art class and writing and Key Club and Prairie Restoration, I made lifelong friends.

But while the social and athletic side of life went well enough, I struggled with some subjects from an early age all the way through college. I would not learn until later in life that I was “blessed” with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. From grade school on I’d crush some subjects and do poorly or fail at others. In that respect, I had great company in an artist that I’d come to admire, one my favorites, in fact. Louis Agassiz Fuertes, a bird painter from the early 1900s. He was an artistic genius who also had a tough time with certain subjects. Here’s a clip from his biography.

That was me, too. I spent far too much class time either drawing or dreaming that I’d “come awake” at some point to the fact that I’d entirely lost the point of discussion. Teachers hated that. Attention deficit was poorly understood back then. I recall my mother having meetings with teachers to discuss my progress through the elementary and middle school years. My mother was a teacher also. She tutored kids at our home during after school hours and once told me, “These children have some learning challenges, so we don’t talk about them at school, okay?”

From fog to clarity

Throughout junior high and high school I felt moments of foglike distraction. It would take over my brain during certain classes, especially math, and of course algebra, a subject that bored and exasperated me. Once you’re behind in that class, you stay behind. I got a series of Ds in high school algebra.

But algebra required a type of executive function and organization at which my brain did not excel. I don’t care.

I did well in geometry because it involved shapes. I picked up a love of perspective and measurements from a seventh grade Industrial Drawing class in which the teacher was an taskmaster. We worked to be as perfect as possible during his guidance. I loved the demanding atmosphere. We took blocks of various construction and mapped them out with precise measurements to draw images on light green industrial drawing paper. Then we carefully labeled our drawings in all capital letters. I started write in all caps in everything I did, a habit that reverberates to this day. It all started in seventh grade.

An able substitute

That brings me to why I’m now a substitute teacher on top of my prime occupations of writer and an artist. As so often it happens in life, our perceived strengths can turn out to be weaknesses, and vice versa. Given the fact that I had trouble learning certain subjects in school and processing specific types of information in the work world, I’ve had a professional career much in keeping with my academic experience. Massive successes accompanied by distracted failures.

Many times I’ve wondered if I chose the right career path at all. About fifteen years ago, during a period when my late wife was fighting cancer and I was out of work taking care of her, I wrote a friend about getting back into the marketing world once she was well enough. In a kind and assertive way, he told me, “You know what? You should be a teacher.”

I’d considered that early in life because my mother was a teacher all her life. So was my brother, and I married a teacher back in 1985. That meant I visited tons of classrooms over the years. While I talked to much in most of those teaching opportunities, I slowly learned that teaching is actually getting students to learn by discussion rather than just telling them stuff. Based on that foundation of understanding, I’ve become an able substitute, certified to teach based on my college degree and education.

Those who can’t do, teach…

Perhaps I was haunted during my college years by a statement someone once made in my presence. It was patently false, but it sank into my conscience and never let go. They said, “Those who can’t do , teach.”

Along with my reading of Ayn Rand,’s The Fountainhead during my early 20s, I’d embraced the idea that creators of any kind cannot compromise their principles by “teaching” rather than doing. In my rebellious youth I came to view the teaching profession as somehow “giving in” or “giving up” on the things I loved to do, especially art and writing.

After watching the movie Mr. Holland’s Opus, I was moved by the character’s struggle to complete a symphony while juggling his commitment to teaching. Along the way, his “work” as a teacher motivated hundreds of students to “try hard things” as so many arts instructors encourage kids to do. That included a woman student who went on to become governor. The movie ends with a surprise performance of his “American Symphony” that encompassed influences from rock to classical music. It symbolized his desires to create and also stood for the advocacy he had for the arts in the face of the music program he loved being cancelled for lack of funding.

What Mr. Holland learned was that he should not be ashamed at having chosen the teaching profession. It did not mean that he “could not do.” Instead his gift was encouraging and demanding effort from others, and ultimately, from himself as well. His life was not perfect, yet some things were perfected as a result of his trying.

Another lifetime

I can’t say that I would have been a great teacher if I’d allowed myself to pursue that profession. I might well have run afoul of administration with my propensity for self-expression and a strong sense of social justice. I’ve known several teachers that were chased out of schools for the same thing. Yet I remain a strong advocate for public education. I believe in it because there is a darkness about privatizing education by allowing it to be taken over by those who want to censor reality in favor of ideology. There’s a genuine threat of that here in the United States of America. I’ve written books about that threat.

So I haven’t wasted my time or opportunity at what I’ve done. But one can imagine what it would be like to pursue a different path in another lifetime. I do have a talent for teaching. Once after an internal presentation at the marketing company where I worked as the Senior Copywriter, the head Creative Director came up and said, “You should do this for a living.”

That was ten years ago. Now that I’m at the age where getting hired in the creative industry is difficult due to factors such as ageism (“He must not be any good if he hasn’t retired yet…”) I am pushing forward with my art and writing. There are still bills to pay, and I learned the hard way that accepting Social Security when you’re earning too much results in penalties. I had to play catchup after eight years of caregiving through cancer survivorship with my late wife. That’s not easy.

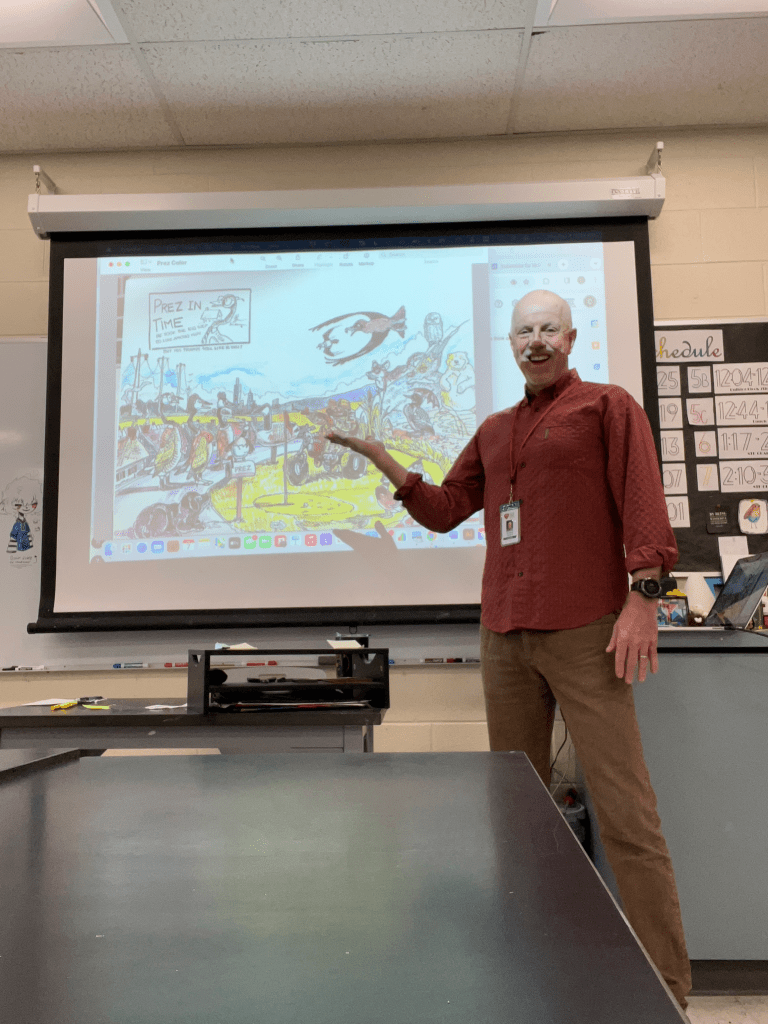

So I’m a substitute teacher because it is the perfect balance of earning income and level of time commitment. Right now I’m in a full-time sub position for an art teacher that tore her Achilles tendon at a trampoline gym and needs a few weeks for rehab after surgery. Over the last three years I’ve taught everything from Pre-K (the age my late wife taught) to Middle School and High School. Every one of those assignments is interesting in its way. The little kids say the darndest things. The middle schoolers try to figure themselves out and the high school kids appreciate if you treat them like actual human beings.

I do love teaching. I’m not afraid to push kids when the subject presents opportunities to learn. I get them asking questions and let them proceed at their own pace at times. I’ve taught kids with learning difficulties, and have great empathy for them given my own academic history. That includes working as a paraprofessional at times, supporting kids one-on-one through the day if necessary, or just watching them so they don’t wander off on the playground.

I’m a substitute teacher because I like it. Grant you, I’ve got retired teacher friends who still help out in the classroom. Others are so done with teaching they never want to go near a school again. So it’s a they say, “To each their own.”

My approach is taking pride in what I’m doing at any given moment. That’s the Right Kind of Pride. We all arrive at circumstances in life from different timelines and varied perspectives. As the ending of the book Candide observes, and I paraphrase, “We must cultivate our own garden.”

And keep growing.